When I was working on my life of Lorca, I often asked myself the question Lear asks, late in Shakespeare’s play, about Cordelia: “Have I caught thee?” It’s the biographer’s essential question: have I managed to transcend time and circumstance and geography to know what makes/made you tick?

I find myself asking it again as I try to make sense of my forebears—the Scarletts of Georgia, who built a small fortune using the labor of human beings they bought and hunted and enslaved. I’m especially curious about the man who started it all—Francis Muir Scarlett, my great-great-great grandfather, who fled from England to Georgia in 1799 and by 1812, at the age of 27, was a plantation overseer, and within another decade, a planter, slaveholder, and state legislator.

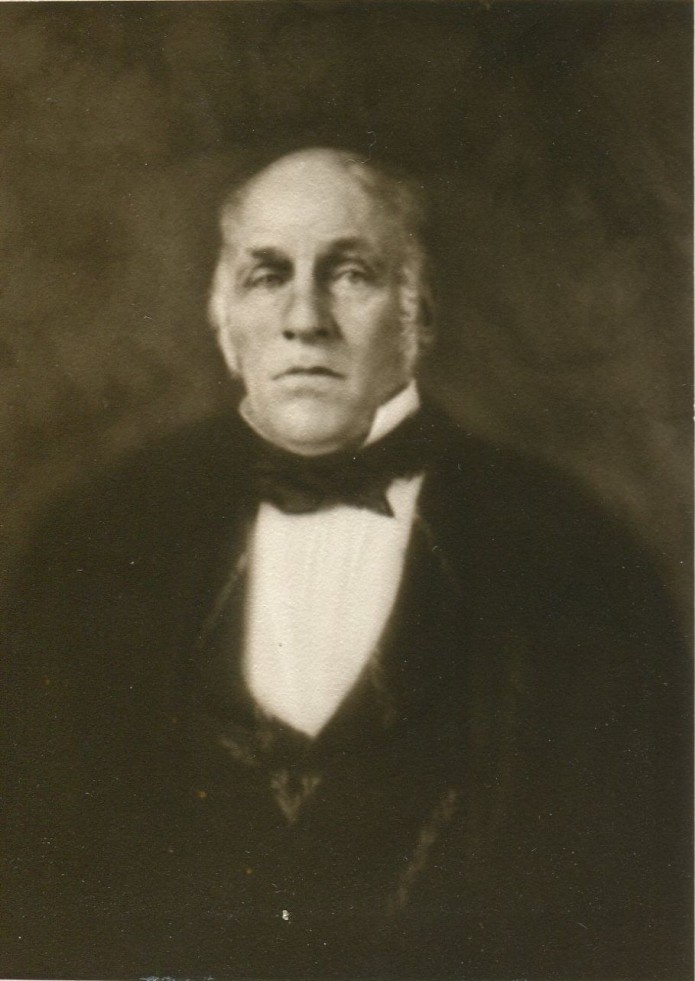

He’s a squirrely guy. I’ve got one photograph of him, above, undated. He left little in the way of a paper trail—mostly legal documents and ads for runaways. But last month I got a tiny glimpse of Francis Muir Scarlett in action.

I was trawling the Journals of the state legislature at the Georgia Archives, outside Atlanta, and found multiple references to Scarlett. One, from 1826, showed him in action, in his “room” in Milledgeville, demanding to know why a fellow legislator—a Mr. Powell, from Darien—had published a private letter. The back story is complicated and involves bank business, but the description of Scarlett caught me:

Mr. Scarlett then rose, got the document, and handed it to Mr. Powell, who read it and made no remark about it, nor evinced any surprise.

There he is, my ancestor, fleetingly alive and in action. I can see him in a firelit room, dark suit and white shirt, black tie, as he brandishes the incriminating letter and confronts his peer. It’s a rare moment.

The state legislature Journals reveal other details: that Scarlett was more interested in infrastructure (canals, bridges, ferries, roads) than in questions of slavery or Native American rights (both of which preoccupied lawmakers in the decades he served). Tto my delight, I learned that Scarlett voted in favor of divorce every time he was asked to weigh in. (For a married couple to divorce, both houses of the state legislature had to authorize it.)

But have I caught Francis Muir Scarlett? No way. Try to fathom why he embraced the slavery business, and I’m stumped. Was it simply circumstance? Geography? Need (or greed?)

Could he have said no? I go round and round, wanting to understand how and why he did what he did. It’s clear he wanted to be wealthy and powerful, and it’s equally clear that in early-19th-century Georgia, those tended to go hand-in-hand with enslaved labor.

And what about the women—Scarlett’s wife, daughters, daughters-in-law? Women confined to parlors and birthing rooms, for whom marriages were arranged and dowries compiled, for whom legal rights did not exist. (When Scarlett’s daughter Mary Ann became a widow, her vast inheritance passed directly to her father.)

Unlike the Grimké sisters or the actress Fanny Kemble, who published a chilling eyewitness account of the appalling conditions on her husband’s Georgia plantations, my female ancestors did not, so far as I can tell, speak out. They clung to the family business, it appears, and to their comforts—as I fear I would have done in their place.

I’m working, still, to catch all of them.